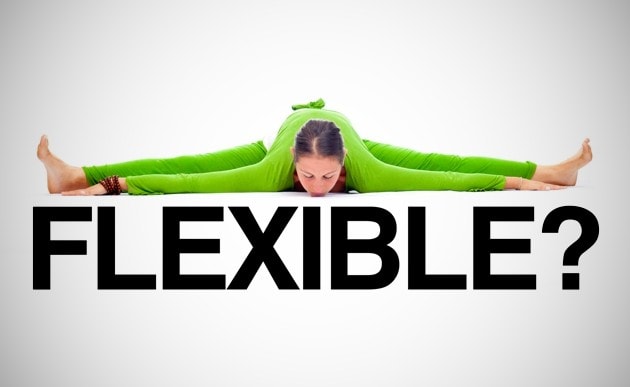

One of the phrases that I too often hear from students new to yoga is “I’m just not flexible enough to be good at yoga.” Then they list examples like their inability to touch their toes in a forward bend or to wrap their arm behind their back in a bind. When I hear this, I let them in on a little known secret: Their so-called inflexibility actually saves them from hurting themselves. In fact, the more flexible you are, the more prone to injury you can be.

I know that logic may sound bizarre coming from a yoga instructor, and sure, when we see hyper flexible people do seemingly impossible things with their bodies in deep backbends or forward bends or complex binds that look like human knots, it can be pretty impressive. However, as a long-time student and teacher, I’ve witnessed the risks of hyper flexibility as well as learned my own painful lessons. Once I’d had severe elbow pain because of a tendency to hyperextend my arms. My body had had enough, and the pain had advanced so much that even backbends like Bridge (Setu Bandha Sarvangasana) where I used to clasp my hands behind my back had become extremely painful for my elbows. So being too flexible can have its drawbacks, too, and at its extreme can open the door to serious injuries, chronic pain and degenerative diseases later in life.

The perks to being less flexible

A human can’t hold his or her breath forever. The body’s natural instinct is to breathe (i.e. live), and it would take a concerted effort, most likely with other instruments involved, to stop breathing. A similar protective instinct is present for the less flexible yogi. A person with a limited range of motion already has built-in obstacles in to prevent him or her from going too far into a forward bend or backbend. For example, a yogi with a tight back, shoulders or hamstrings most likely cannot push or pull into the deepest variation of Bow (Dhanurasana) or take the arm bind and deepest hip opener in Cow’s Faced Pose (Gomukhasana) without actively ignoring the internal sirens signaling to stop. So they can avoid injuring themselves because of these limitations.

On the other hand, for hyper flexible people, a.k.a. hypermobile, those built-in checks and balances are not overtly present. Instead, these yogis can more easily reach for the big toes in a forward bend, perhaps easily drop back into a Wheel (Urdhva Dhanurasana) or hang out in a deep hip opener like Lotus (Padmasana) without much of a warm-up. These yogis tend to have hypermobile joints, and may overly rely on the connective tissue to do much of the stretching. Unfortunately, this can continually weaken the surrounding muscles, tendons and ligaments, the last of which don’t have a whole lot of capacity to stretch or contract since their main work is to stabilize joints. So hypermobile yogis can keep pushing or pulling until something wears, tears or breaks, which can mean a long, sometimes painful, recovery.

A lesson in mindfulness on the mat

As extreme as the cases for the hyper flexible and the flexible yogis may seem, they both can use the same measure of mindfulness, patience and humility to practice happy. When too much of a good thing can turn bad, and too little of a good thing can make you feel like you’re always missing out, that leaves only one answer. Aim for somewhere in the middle to find an equal measure of strength and suppleness to cultivate resiliency for your body and mind.

Through the frustration and deep worry of my own bout with hypermobility issues, I’d realized I hadn’t been practicing mindfulness in my yoga leading up to the injury, and things needed to change if I hoped to overcome the roadblock. I rested and modified movements to allow my body to heal. But then I also reviewed some of the yamas, a.k.a. self-restraints, in the Yoga Sutras. These four in particular offered me insight and a way to alter my approach on my mat. It’s a lesson, I suspect, we as yogis can use again and again.

1. Ahimsa or non-harming

Treat your whole body like a cherished friend, rather than something to conquer. This can save you from a lot of unnecessary injuries.

2. Satya or truth

Be present and honest about your body in the moment. Our bodies feel different every day. Sometimes we’re dealing with an injury or we’re tighter or more tired than the day before. Try to allow for whatever comes up and move accordingly.

3. Asteya or non-stealing

We all know about the ego, the one that gets you to ignore warnings in favor of projecting a perfect image. I call this trying too hard to take something that doesn’t necessarily belong to you (i.e. stealing). Try to resist the ego. For the hyper flexible, just because you can go to the max, doesn’t mean you always should. Listen to your body to see if you might be relying on joints to do the work, rather than the muscles and bones. For the less flexy, remember your body’s first aim is protecting you from injury, so listen and be patient. You may not ever reach your toes, but you won’t injure your back or hamstrings trying to force it to happen either. Fewer medical bills are nice.

4. Aparigraha or non-attachment

Try to ditch the attachment to what you should look like or how deep you should be in a pose. Some boundaries can be good learning tools! For example, though yoga props sometimes get a bad rap because they might seem like training wheels, nothing could be further from the truth. Props are there to support, enhance as well as help prevent you from harmfully straining to move deeper into a pose. Even if you don’t always use them, don’t hesitate to try out blocks or straps to explore how they can encourage stable, healthy alignment for you.

Next time you roll out the mat, think about layering these into your practice, and feel free to share what comes up!

Pose Therapy is a weekly column by Zainab Zakari that covers the challenges of yoga practice and how to master them. Do you have a yoga problem that you want us to cover? Comment below or email Zainab.