Just as there are many faces of the Buddha, there are many faces of yoga. There are several different types of practices that attract different practitioners. You have the Yin yoga devotee with lotus flowers weaved into her long braid that cascades down her willowy frame, and pools into a perfect Om shape.

Or the kick your asana Vinyasa enthusiast who can hold a Handstand for 11 minutes before floating back into Peacock, and then pushing back up into a Levitating Scorpion. Not every yogi has the same approach, and the more the community grows, the more variations arise.

The Western Incarnations of Yoga

When Hatha yoga was introduced to the American public in the late 40s, Sivananda and Iyengar yoga were the main methods in the early stages. Ashtanga Vinyasa gained popularity in 70s, but for many decades there wasn’t the smorgasbord of options there are today.

Yet in the past 10 years, a huge assortment of classes have become available, ranging from stoned cannabis yoga, to co-ed naked yoga, to yoga classes you can take with your dog, to yoga raves, to karaoke yoga where you can air guitar in Reverse Warrior.

There is even a practice called ‘voga,’ where you can yoga and vogue at the same time.

Within this wide spectrum of Western yoga, I have come across many yogis who have a very proprietary perspective. Even though yoga practitioners are supposed to be accepting and open-hearted, I have heard many passionate opinions about what is or isn’t yoga.

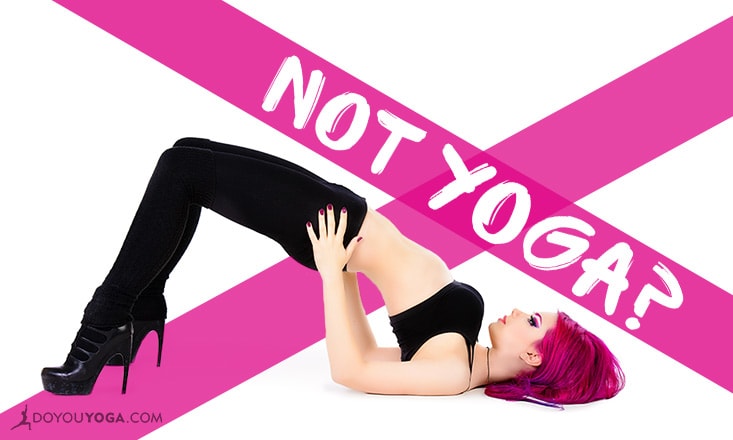

When I heard about yoga in high heels I admit that I rolled my third eye. Yet, what makes one yoga approach more legitimate than the next?

Even though I am pretty sure yogis in early India weren’t taking “yoga on a paddleboard” classes, isn’t all Western yoga a hybrid interpretation of these ancient teachings?

On Traditional and Non-Traditional Yoga

"Traditional yoga" is one of the six schools of Indian philosophy and was historically taught orally from guru to student. The doctrines were typically communicated in sutra style, and outlined in 196 of the Yoga Sutra.

Yoga was not a physical practice with a spiritual suggestion, but rather a spiritual practice with a physical component. There was no yoga on and off the mat, because as a yogi your entire life was yoga—I am also pretty sure there were no synthetic yoga mats five thousand years ago.

In the past framework, the asana were part of a much greater system that was very heady and intricate. Yet the modern understanding is that the asana are yoga, and the teachings are a compliment to the postures.

Many people who are long-term disciples know this need to study the many sacred texts, but I think an extremely small percentage fully practice in the same capacity as the original teachings.

Although it is easy to look down our noses at some of these emerging forms as “not being yoga,” technically what 99.99 percent of us do isn’t either. Regardless of our intentions, we are still engaging in a modern variation that cannot be divorced from the context in which we exist.

A Practice of Constant Evolution

Rather than labeling these emerging adaptations as yoga or not yoga, why not embrace fully the ever evolving nature of the practice?

In current times, where we spend so much of our lives being sedentary, there is going to be a greater interest in asana simply because our bodies are so neglected. If we were living a few millennia ago, we wouldn’t need to exercise our muscles as much because we would have just walked 18 miles for water.

Even if what is happening now isn’t considered traditional yoga, that doesn’t mean it isn’t valid or helpful. Not everyone is going to read all the ancient texts, or have a personal relationship to the philosophies beyond the passing comments heard by teachers.

There are millions of yogis who haven’t read the Bhagavad Gita, but that they do heart openers every day still makes them a different person. In an ideal world, there is deeper integration of the mind and spirit within the body, but if asana open up the door, then that is a good start.